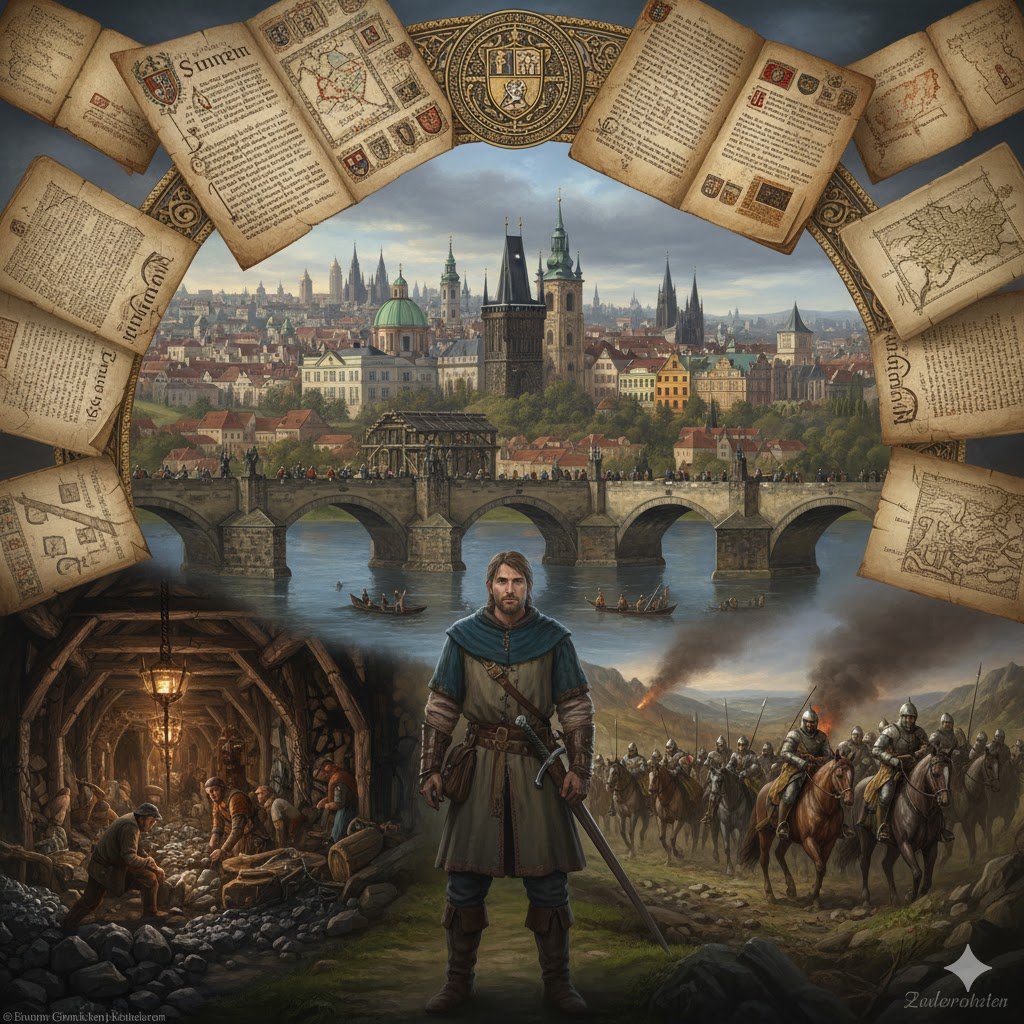

Whenever someone asks me what my favorite video game is, I often have a hard time choosing, but two games that often pop into my head are Obsidian’s Pentiment and Warhorse’s Kingdom Come: Deliverance. Now, being a medievalist, it’s probably no surprise that these two come up, though I have been told by non-medievalists that these are pretty good games too. So, it’s probably not just that, but as a medievalist, the history is indeed an important part, and it’s one of the things that brings me back to these games and helps me feel immersed in them. In this blog, I will talk about the history (The Real History) behind my favorite game.

The Holy Roman Empire:

Now I get the feeling that a good chunk of my audience knows what the Holy Roman Empire was, but because I’m sure that there’ll be plenty of people coming to this video because of the game, who aren’t as familiar with history beyond what they learned in high school, I’ll explain it very briefly.

Simply put, the Holy Roman Empire was, for the most part, medieval Germany; it also encompassed Italy, the Netherlands, and other places that aren’t part of Germany, including Bohemia, but it was dominated by German princes, and the Emperors were almost always German.

In the Middle Ages, it was seen as the successor to the classical Roman Empire, which people typically call the Roman Empire, and the emperor was crowned by the Pope, hence the Holy Roman Empire. The emperor was also elected from amongst the princes of the empire, that is, the powerful rulers of territories within the Empire, though the children of a previous Emperor were often given priority. When one was elected, they were crowned King of the Romans until they could be crowned by the Pope in Rome, at which point they became emperor.

Bohemia’s Rise:

So then what is Bohemia? Well, Bohemia is a land largely defined by the Bohemian Basin, which is today part of Czechia or the Czech Republic, alongside Moravia, which is also relevant. To properly understand it, and especially its relationship to the Empire, we have to go back a fair bit.

The area of Bohemia was settled by Western Slavic peoples, the future Czechs, who assimilated the local populace and established various chiefdoms in the sixth to 7th Centuries. By the late 8th Century at the latest, the Frankish Kingdom, predecessor of the Holy Roman Empire, bordered this region and saw many of these Western Slavic lands as Frontier lands within the Frankish sphere of influence and areas for potential.

Eastern expansion. The Franks regularly tried to establish hegemony over them while also sending missionaries to convert them to Christianity. However, in the 9th century, a West Slavic state known as Great Moravia, encompassing later Moravian parts of modern Slovakia, Austria, Hungary, and Poland, came to dominate Bohemia instead, and it was actually officially ceded to Moravia in 890, though it had been under Moravian influence for a while by then.

Nonetheless, Great Moravia began to weaken and collapse in the 10th century, and the Bohemian Basin started to be dominated by a powerful Czech Dynasty based in Prague. The Premyslids of who were in the middle of the century, Bohemia would once again be subjugated by the Germans under Otto, and the Premyslids would be known as the Dukes of Bohemia, subject to the Empire.

In the 11th century, Bohemia would come to take over what we now call Moravia, which was only a fragment of the former Kingdom. For the next two centuries, it would usually be ruled by members of the Junior branches of the Premyslids dynasty. During this time, Bohemia would also have a back-and-forth relationship with the Empire, with some Dukes getting quite powerful and having their power checked by Emperors worried by their autonomy, while others worked closely with the Emperors as allies.

Like, when Emperor Henry II relied on Bohemia to help him check the ambitions of Boleslav of Poland, with Poland being in a similar situation as Bohemia, though in the end, more successful at growing strong enough to assert its independence from the Empire. Likewise, Vratislav II of Bohemia helped Emperor Henry IV in his conflict with the papacy and internal rebellions, which led the emperor to grant Vratislav the title of King, though this wasn’t hereditary.

By the end of the 12th century, the Empire’s political struggles and internal weakness allowed Bohemia to thrive independently, and its Dukes became some of the most powerful princes of the empire. Its strength and importance led Frederick II to elevate its rulers to the rank of hereditary Kings in 1212. This was only the beginning of Bohemia’s era of growth.

As the electorate of the empire was being constricted to a smaller number of princes, the kings of Bohemia had their place solidified amongst them. King Otakar II was even a candidate for Emperor, though his great deal of power and military conquest actually worried enough of the electors that they chose the first Habsburg, Rudolph I, instead. And Otakar actually died in battle against Rudolph.

German Immigration and the Mining Boom:

Another development with a long-lasting legacy, and one which is especially significant for the context of Kingdom Come Deliverance, was the further integration of Bohemia into the Western European institutional and technological sphere under Otakar II. Especially German immigrants were enticed to settle in forested and underdeveloped parts of Bohemia with Promises of land ownership and various rights, while also being allowed to be governed by German law. Several new towns were established, especially in Moravia, and Germans also established themselves in existing ones, often helping them grow.

With them, the Germans also brought various Customs which helped develop Bohemian urban activity, like trade and certain crafts often dominated by these very Germans, who also gave Bohemia a significant Burgher class for the first time. By 1403, though the Czech Burger class had also grown to the point where Czechs now dominated most towns in Bohemia, with the notable exception of the Old Town of Prague and a few others, though there were still Germans in most towns, and they retained prominence, especially in Moravia and Silesia.

A similar process also took place in Poland and Hungary, and there were also many Jews who came along, which is why this region has had such a large Jewish population for centuries. Expanded whenever they took in refugees expelled from other parts of Europe, and Prague especially had an important Jewish Community.

Anyway, one area of craft expertise brought into Bohemia by German immigrants was in modern mining techniques, which would have a huge influence on the kingdom, as the Kings would invest heavily in the mining of silver, which was abundant in the area and would become Bohemia’s most important export. In fact, Kutná Hora, which is a prominent location in Kingdom Come: Deliverance 2, was founded around this time after silver began to be mined there sometime around the 1260s to 1280s, and had a significant German population.

Indeed, Skalitz, Henry’s Home, was also a center of silver mining established in the 1300s, which is important both for the game and the history behind it.

The Luxembourg Dynasty and Charles IV’s Golden Age:

But anyway, by the time of Kingdom Come Deliverance, the Premyslids were no longer Kings of Bohemia. Wenceslas IV was a member of the Luxembourg Dynasty. Now, what does Luxembourg have to do with Bohemia? Well, in 1308, the Count of Luxembourg, Henry, was elected King of the Romans as Henry VII. He was the emperor that Dante left an empty seat for in heaven, seeing him as a divinely sanctioned savior of the Empire and of Peace in Italy, but who the Italians foolishly refused and resisted.

He also happened to be the Emperor around the time that Bohemia was having a succession crisis. Wenceslas II died in 1305, and his son Wenceslas III was murdered the following year, dying without an heir. The Dukes of Austria and Carinthia then fought over the succession, both basing their claims on marriage to Wenceslas III’s mother and sister, respectively. Ultimately, Henry of Carinthia would rule after Rudolph of Austria’s death in 1307.

But the new king got along so poorly with the Nobles and Elites of Bohemia that they began negotiating with the emperor to replace him with the emperor’s 14-year-old son, John, on the condition that John marry Wenceslas III’s sister, Elizabeth.

Now, by the time Luxembourg ruled, the nobility of Bohemia was powerful and entrenched, and it was very difficult to rule without their help and cooperation. And after his father died in 1313, John had a hard time with it. Conflicts with the nobility led him to rule Bohemia from afar, staying instead in Luxembourg and leaving much of the day-to-day Affairs to the Bohemian Barons.

But that would change with his son, Charles IV, who not only ruled the kingdom from Prague after his father’s death in 1346, but the Empire as well after the death of Ludwig the Bavarian the following year. Charles had, generally speaking, a much better rule and a much better time dealing with the Bohemian nobility, though not without any issues. He managed to elevate the kingdom to a position never before seen, and Bohemia was, for the first time, a kingdom whose importance went beyond the Empire and its other neighbors, Poland and Hungary.

Now, the English, the French, and even the Ottoman Turks were paying attention. Prague became the center of Imperial political power, but also an important center of art and culture, and after its foundation in 1348, its University made it an important center of learning as well. In fact, the university became the central educational institution of the Empire and was also attended by many Polish, Hungarian, and even Scandinavian students.

The artistic and scholarly context of Prague likewise helped in the burgeoning of a vernacular Czech literary culture, and both original works and translations into Czech became more common; even German literature got a boost in Bohemia.

The Dawn of Reform:

The university also became a center for religious reform movements. There had been a general sentiment in Europe, especially since the Black Death in the middle of the 14th century, that the whole of society, and especially the Church, was in dire need of moral reform; that the clergy were too tied to their vast worldly possessions, and this was coming at the expense of their spiritual responsibilities, especially toward the common folk.

One man who spoke to this resentment was an Englishman, an Oxford scholar named John Wycliffe. Among other things, he argued that monastic communities were corrupt and evil, and that many in the Church who professed the faith were nonetheless wicked and destined for hell. He also argued that the words of such men, even if they were bishops or popes, were worthless, and opposing their doctrine was permissible. Wycliffe was controversial, and he would be posthumously declared a heretic in 1415. By around the 1380s, however, his work became rather popular in Prague, brought back by Prague students who had gone to study for some time at Oxford. In fact, we have more medieval manuscripts of Wycliffe’s works surviving in Bohemia than in England.

The most famous of the Wycliffe-inspired Prague reformers is without a doubt Jan Hus, whose execution as a heretic in 1415 would kick off the Hussite Rebellion, or revolution, depending on how you frame it, after Wenceslas IV’s death in 1419. By 1403, though, when Kingdom Come Deliverance takes place, he was relatively new to the face of the reform movement. It was not yet as radical as it would later become, but it did call for the Church to desacralize, giving up its wealth and worldly possessions in order to focus on the spiritual well-being of the people.

Hus saw the Church’s role as being the moral guide of the world, even influencing politics and royal decisions, but it could not rightly do that while it was so involved in worldly affairs, too focused on what it could gain for itself rather than for the souls of the faithful. In 1402, Hus was appointed as the preacher of the Bethlehem Chapel in Prague, which had sermons exclusively in Czech. The post-plague period had seen a large growth in personal devotion and connection to the faith among the laity, and for many, topical sermons in their own language spoke directly to that desire. This helped grow Hus’s popularity and explains why Father Godwin knows about him and discusses similar reforming ideas when you speak to him in the game.

But getting back to Charles, he died in 1378, leaving Bohemia to his son Wenceslas IV. Yes, he died 25 years before the events of Kingdom Come: Deliverance. I specify that because the way it is mentioned in the game’s intro cinematic made a lot of people think it was much more recent than it actually was.

Wenceslaus IV’s Troubled Reign and Internal Conflicts:

Anyway, Wenceslas also became King of the Romans at the time, since he had been elected two years prior, thanks to the efforts of his father, which included him basically buying the margraviate of Brandenburg and giving it to Wenceslas, which made him one of the electors. When Wenceslas became King of Bohemia, Brandenburg then went to his half-brother Sigismund, who we’ll get back to later.

At the start of his reign, Wenceslas basically only had control of Bohemia, Cieszyn, and Lucca, all of which had been brought into the Crown of Bohemia by John and Charles. Moravia, though, was ruled jointly by Wenceslas’s cousins Jobst and Procop, who often fought for dominance but sometimes worked together. Luxembourg was ruled by his uncle, Charles’s brother, also named Wenceslas. Wenceslas IV inherited it after his uncle’s death in 1383, but he later gave it to his cousin Jobst in 1388 in exchange for a substantial loan. Sigismund did the same with Brandenburg in the same year. All that to say that Wenceslas relied on Bohemia as his power base, so the problems in Bohemia became big problems for him.

Now, Wenceslas’s reign started off rather promising. His father had given him a good education, and he frequently attended court growing up. Wenceslas continued his father’s efforts to support art, culture, and education in Prague. But it soon became clear that the king wasn’t nearly as interested in other aspects of governance. He spent most of his time in provincial royal castles, away from Prague, and his love of hunting became a focal point of his critics, who called him lazy or idle. He was also apparently prone to mood swings and may have been an alcoholic.

Now, some of the problems weren’t entirely his fault. Things hadn’t been all that rosy at the end of Charles’s reign. There was economic stagnation, possibly due to Bohemia being hit by waves of plague later than much of the rest of Europe, though the full extent of the causes isn’t entirely understood. There was also a rise in conflict between the upper nobility and the Empire, and the towns and lower nobility. Finally, there was the Great Western Schism, which started a few months before Charles’s death. After almost 70 years of the popes residing in Avignon, where they were greatly under the influence of nearby France, a conflict emerged, which led to there being two popes simultaneously, one in Avignon and one in Rome, both competing for legitimacy and being backed by the various states of Catholic Europe, a situation which would only be resolved in 1415.

Wenceslas’s lack of diplomacy and finesse made it hard to deal with these issues. In fact, he was infamous for avoiding difficult decisions, something which is important for a monarch. As ruler of the Empire, he was expected to do something about the papal Schism. Although he declared favor for the Roman Pope Urban VI, this was only after the new Archbishop of Prague had already done so, essentially deciding for him. Urban then invited Wenceslas to Rome for his imperial coronation, an event which would have legitimized both parties, but Wenceslas just never bothered.

A lot of people blamed this on his laziness, but it might also have been because he recognized that his position at home wasn’t secure. Going on a many-month-long journey to Rome and back might have been dangerous. As I said before, the nobility in Bohemia was strong, and Charles didn’t change that. Charles relied on his ability to build strong ties with them in order to get them to cooperate, but Wenceslas struggled with that. Instead, he relied heavily on landowning commoners, burghers, and members of the lower nobility, for example, Radzig, who was granted Skalitz in 1403 and appointed Royal Hetman, basically commander of the army. But this just wound up annoying the upper nobility even more.

Tensions exploded after 1393, when Wenceslas fought with the Archbishop of Prague and had the cleric John of Nepic drowned. The exact reason for this varies from tale to tale. In 1394, several disgruntled nobles formed the League of Lords, headed by Henry III of Rosenberg, with the Rosenbergs being one of the most powerful noble families in Bohemia. The League allied itself with Wenceslas’s cousin Jobst of Moravia. It then had Wenceslas imprisoned, but pressure from the pope, the German princes of the Empire, and Wenceslas’s half-brother John of Görlitz, who raised an army and occupied Prague, led them to sign an agreement where Wenceslas was released under the condition that he guarantee certain rights to the lords.

Despite this, fighting between the factions continued until a peace could be negotiated with the help of Wenceslas’s other half-brother, Sigismund, in 1401.

The Empire Deposes Wenceslaus and Sigismund Seizes Power:

In 1401, for one thing, the German princes were also getting fed up with him, especially his lack of ability or willingness to keep peace in the Empire, and his inability to mend the papal Schism, which by now had gone on for over 20 years. Both original popes involved had died and been replaced, indicating that the situation wasn’t just going to resolve itself anytime soon.

In 1400, four of the Imperial electors, the Count Palatine Rupert and the archbishops of Cologne, Trier, and Mainz, declared that they were deposing Wenceslas and elected Rupert to replace him. Wenceslas, or someone around him, realized that the best way to deal with this might be to finally go to Rome and be crowned Emperor, especially since the Roman Pope was hesitant to recognize Rupert’s election. But having just created a fragile peace at home, he decided to place his half-brother Sigismund in charge as regent while he was away.

When Rupert heard about this plan, he sent his army to block Wenceslas’s passage to Italy. This is where we finally talk about Sigismund. After hearing about Rupert’s maneuver, Sigismund decided to take advantage of the situation. By now it was 1402, and with the support of the League of Lords and the Duke of Austria, he kidnapped Wenceslas and imprisoned him in Vienna, forcing his brother to sign over royal power to him.

By 1402, Sigismund was King of Hungary and Croatia, having married the heiress to the kingdom, Mary, in 1385, three years after her father, the Old King Louis the Great, had died, and being crowned in 1387. Now, don’t let the size difference between Hungary and Bohemia deceive you, Sigismund’s position as king was also quite precarious. Much like Bohemia, the lords of Hungary were quite powerful and autonomous. On top of that, Sigismund’s kingship through marriage to Mary put him in a shaky position with many of them from the start, and that only got worse when Mary died in 1395 without a living child.

Sigismund had an opportunity to improve his position by leading the crusade that had been called against the Ottoman Turks, who had conquered much of the Balkans and whose territory now stretched almost to Hungary’s very doorstep. Many Christians saw the Ottomans as an existential threat to Christendom, and the army that amassed in Buda was one of the largest Crusader armies ever assembled.

But the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396 was a disaster for the Crusaders and would be a permanent stain on Sigismund’s legacy. More immediately, it further soured his relations with the Hungarian lords, some of whom formed their own league and actually imprisoned him after his return from Bohemia, following the peace negotiations he helped mediate in 1401. Even some of his former supporters had turned on him.

Sigismund’s decision to depose Wenceslas wasn’t that of a powerful ruler bullying his weak neighbor. It was an attempt to take advantage of an opportunity in order to build up a reliable power base when he severely lacked one.

Sigismund’s Precarious Position and the Role of Cumans:

Now, one way that Hungarian kings had historically tended to get around relying on their nobles was with the help of Cumans, something which is depicted in the game. I’d like to talk a bit about them as well. The Cumans were historically a highly diverse confederation of nomadic peoples living in the steppes of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, whose land stretched up to the Carpathian Mountains near Hungary.

In the early 1200s, however, they were defeated by the Mongols, and a few groups under several of their khans were given the right to settle in Hungary in exchange for service to the king, especially military service. They largely settled in the Hungarian plain, where the local population had been most decimated by the Mongol invasion of Hungary, and they remained a distinct ethnic group within the kingdom for centuries.

When they initially settled there, they had to pledge loyalty to the king, which established a special relationship between them and the kings of Hungary. Because of this, some kings relied on them extensively, feeling that their loyalty was more secure than that of their nobles. This sort of arrangement was common with many minorities and perceived outsiders in the Middle Ages, who relied on kings for status and whom the king felt he could trust more than the entrenched aristocracy. Many monarchs saw Jews this way, and Spanish and Sicilian rulers sometimes used Muslims in the realms, or from just outside the realms, to a similar effect. Soldiers thus became an important part of the Hungarian king’s army.

Now, although Sigismund’s father-in-law, Louis the Great, used them, references to such units fade by the end of his reign. Sigismund instead implemented a system whereby landholders across his lands had to provide one light cavalryman with a bow per 20 peasant plots on their lands, with smaller landholders combining their means to support a single soldier, a system known as militia portalis. In practice, due to his weak power base at the time and the fact that the Cuman lords remained generally more loyal to the king, many of his troops in Bohemia were probably Cumans, but not all of them.

Cumans would have been nearly as distinct from non-Cumans in 1403 as they had been back in the 13th and early 14th centuries. By this point, the Cumans had long since adopted a sedentary lifestyle, though archaeological evidence and administrative records indicate that pastoralism and horsemanship remained important. They had also been gradually adopting more typical Hungarian clothes and habits and were becoming more integrated into the wider Christian community. Previously, they had retained many practices that were deemed pagan by Church authorities, like sacrificing dogs and swearing oaths on their bodies. There was thus a long, determined effort to get them to conform to what was seen as proper practice, something which was indeed ongoing in the 15th century.

Cumans retained a unique identity among Hungarians, with certain customs that distinguished them from other groups, but they wouldn’t have seemed much more foreign in Bohemia than any other Hungarian soldier. The way they’re presented in the game is much closer to what you’d expect from the Cumans fighting for Louis IV, for example, in the late 13th century, when he helped Rudolf von Habsburg defeat Otakar II of Bohemia. That said, they would still have been using sabers and recurve bows, since these were becoming more popular with Hungarian light cavalry at the time, in part a holdover from Cuman influence, especially regarding the bows.

Also, the reputation they have in the game as bloodthirsty pagans does reflect, to an extent, how they were long perceived, again partly due to their long history of retaining pre-Christian customs, which were deemed problematic by the Church, and the stereotypes that went along with that. Likewise, they speak Hungarian in the game, which is a nice potential nod to their integration into Hungarian society, though it might also just be a practical matter, since we don’t have enough preserved sources to fully reconstruct their original language for in-game use.

The Attack on Skalitz:

Anyway, but now let’s get back to the conclusion of our narrative. In 1402, Sigismund brought his army to Bohemia and began attacking Wenceslas’s supporters and allies in order to secure the throne.

In order to support his army, he imposed heavy taxes on towns and monasteries. When Kutná Hora refused to submit, he attacked the city, forcing its inhabitants to accept his authority and seizing the silver from its mines.

In March of 1403, he attacked Skalitz, which likewise had a silver mine and was under the care of Wenceslas’s hetman, and therefore an ally of Radzig Kobila. And there begins the story of Kingdom Come: Deliverance.

Eventually, Jobst of Moravia would join Wenceslas’s supporters, which we see at the end of the first game, and is sort of the catalyst for the story in the sequel.

Wenceslaus’s Escape and Loss of Power:

Ultimately, by that summer, Sigismund’s army would be forced to retreat from Bohemia, and Wenceslas would escape Vienna in November and return home. But the king still struggled to hold on to power and would have to make all sorts of sweeping concessions, which effectively made him powerless outside of his direct domains. The pope also came to recognize his deposition and Rupert’s election.

Rupert’s attempt to mend the papal Schism actually only made things worse. In 1409, he elevated a third pope, while both of the others refused to step down, and he died in 1410. There was then a contested Imperial election where both Jobst and Sigismund were elected, but this was effectively resolved when Jobst died in 1411. Sigismund was then reelected, with Wenceslas finally accepting his own deposition and voting for his half-brother in exchange for Sigismund guaranteeing Wenceslas’s right to the Bohemian throne.

Now, I could keep going and talk about Sigismund ending the papal Schism, executing Jan Hus, and the Hussite Wars starting after Wenceslas’s death a few years later. But by now, we’re well past the events of Kingdom Come: Deliverance, and I want to go back to playing it. Hopefully, this historical context will give you a better appreciation of the story and setting of the game.

Conclusion:

Kingdom Come: Deliverance does more than entertain, it immerses players in a complex and turbulent period of Bohemian history. From the rise of powerful dynasties to the intrigues of Wenceslas IV’s reign, the game reflects the political, social, and cultural realities of early 15th-century Bohemia. Understanding the real events behind the story, from Sigismund’s ambitions to the role of Cumans and the silver mines of Skalitz, adds depth to the experience and shows how historical context can enrich gaming narratives.

FAQs:

1. How historically accurate is the game?

Mostly accurate with some creative liberties for gameplay.

2. Who was Wenceslas IV?

King of Bohemia and central to the game’s story.

3. Who were the Cumans?

Nomadic soldiers allied with Sigismund in Bohemia.

4. Why was Skalitz attacked?

Sigismund wanted control over its silver mine.

5. How is Bohemian society shown?

Divided among nobles, burghers, and peasants.

6. Are locations like Kutná Hora accurate?

Yes, towns and mines reflect historical reality.