Our brains can remember a ton of stuff. We can recite the lyrics to our favorite songs years after we learned them. Celebrity gossip and memes live rent-free in our heads. Not to mention the stuff we take for granted, like recognizing tens of thousands of words without issue. If we treat our brains as computers, they can hold 55 million e-books’ worth of information. Which is wild. But what if we could replace our squishy human brains with something else? Say, a bunch of hard drives, or the latest cutting-edge data storage technology. Could we cram even more info in our heads? And if so, is there a limit to how much we can pack in there?

Quantifying Brain Storage:

As a baseline, let’s re-examine how much info our brains can store as-is. To do this, we’re going to analyze our brains as though they’re computers. This isn’t the most perfect approach, but it makes the math a whole lot easier. In a computer, information is stored using a fundamental unit called a binary digit, or bit for short. Each bit can be in one of two states: a 0 or a 1. As you add more bits, you can store exponentially more info. So two bits can store 2^2 or 4 states: 00, 01, 10, and 11. Three bits can store 2^3 or 8 states. Four bits can store 2^4 or 16 states, and so on.

To store information, we can map different states to different numbers or letters. Originally, these individual characters were represented by a block of 8 bits. For easy bookkeeping, this 8-bit block was named a byte. Both terms have stuck around, so sometimes we quantify information in terms of bits, abbreviated with a small ‘b’, and other times we use bytes, with a big ‘B’. This is a situation ripe for mistakes. But alas.

Now, back to our brains. Scientists have tried to quantify how much information our brains can store by finding the brain’s version of a bit. And a really good equivalent is the synapse. A synapse is the interface between two neurons, and its job is to communicate information between them. It does this by continuously transmitting chemical or electrical signals and modulating their strengths.

So if we treat the different signal strengths as different information states, we can determine how many bits a synapse can store. Using a combination of neuroscience and computer information theory, scientists have estimated that a single synapse can store between 4.1 to 4.6 bits of info. On average, a human brain has 250 trillion synapses, which means our brain can hold 143 terabytes of info. If a typical e-book is 2.6 million bytes, that’s about 55 million e-books.

Digital Hardware Comparison:

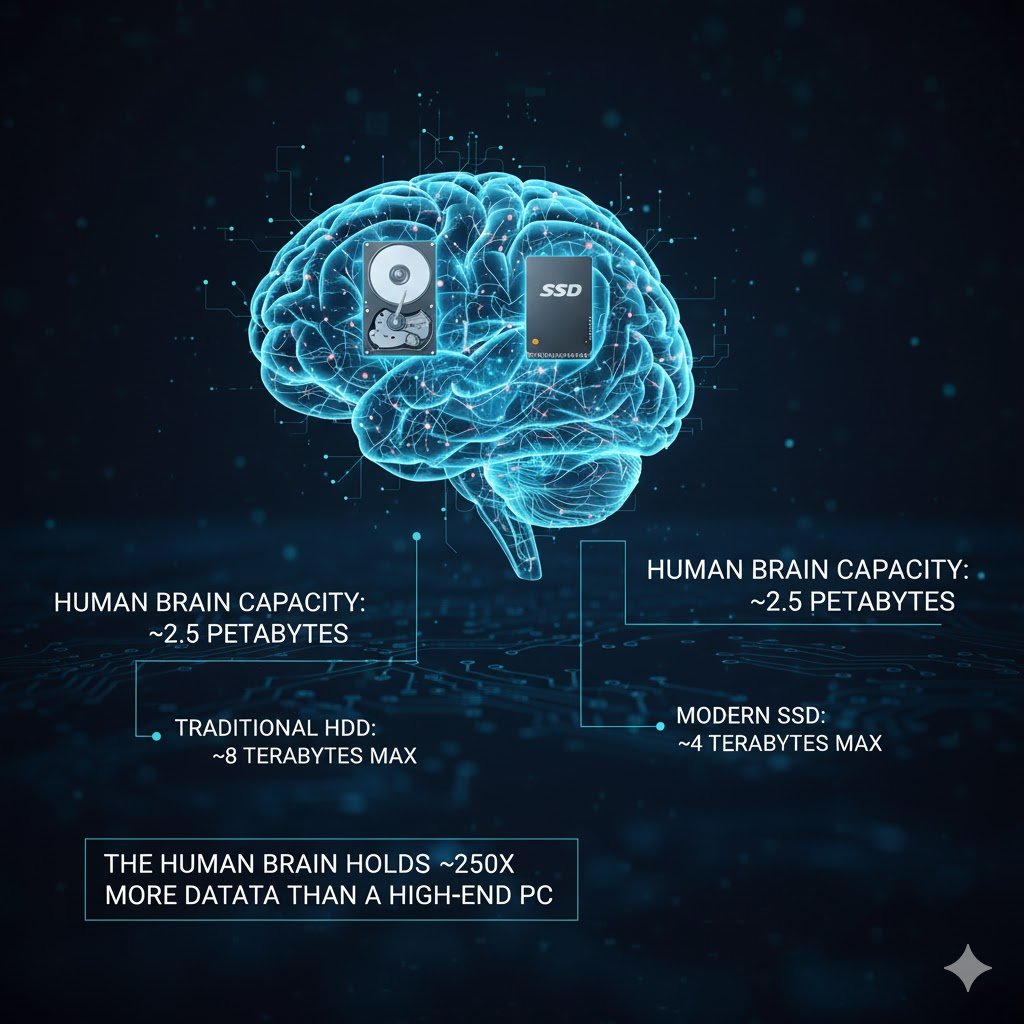

But what if we could replace our brains with actual computer parts? How much information can we store? To start, let’s try swapping out our brains with a hard disk drive or HDD, which is what many computers use to store their data. HDDs get their name because they store data on a spinning disk or platter coated with magnetic material. This platter is divided into lots of tiny, tiny sections that each represent a bit. And each section can be magnetized in one of two directions, which correspond to either a 1 or a 0.

To store data, a needle called a read-and-write head moves to a specific section and generates a magnetic field to change the bit’s magnetization. Now, to estimate how much HDD storage we can cram in our brains, we need to know both their physical and data sizes. HDDs usually come in a standard metal box that’s 147 millimeters by 102 millimeters by 26 millimeters. And right now, one of the highest-capacity HDDs on the market is the Seagate Exos Mozaic 3+, which can store 36 terabytes of data. Although you’ve got to be a fancy data center or business to buy one.

But supposing we could get our hands on those data-dense HDDs, if we pack them into the same volume as a human brain, we would be able to hold 120 terabytes of data. Which is worse than what our actual brain can do? Maybe we should be replacing computers with brains.

But wait! HDDs aren’t just pure data storage. They also include auxiliary parts that allow us to access and edit the stored data, like the read-and-write head. If we throw these parts out and pack in just the platters, we won’t be capable of having dynamic thoughts. But we can store around 1.2 petabytes of data, around eight times more than our actual brains.

But if you’re a stickler for being able to access your data and have actual thoughts, we can look at a different form of computer data storage: the solid-state drive, or SSD. SSDs store data using a grid of electrical switches called floating-gate transistors. Each transistor stores one bit of data by filling or emptying a reservoir, a.k.a. a gate, with electrons. A filled or charged gate turns the transistor “off” and represents a 0, while an empty or discharged gate turns the transistor “on” to represent a 1.

SSDs are an alternative to HDDs that promise high data storage densities, with the caveat that they also have a limit to how many times we can write to them before they stop working. In other words, it’s probably not a good idea to use them inside the head of a person continually updating what they know about the world. SSDs come in all sorts of shapes and sizes, including the same standard metal box that HDDs come in.

But if we’re shooting for high data density, the way to go is the thin M.2 form factor, commonly used in laptops. One of the most data-dense M.2s is the WD Black SN850X. This SSD can hold 8 terabytes of data in a space roughly half the size of a standard ID card. If we were to pack these into a human brain volume, we could store 1.6 petabytes of data, which is equivalent to 600 million eBooks. That’s 30% more than just cramming in HDD platters, and we can still access our data.

Beyond Conventional Storage:

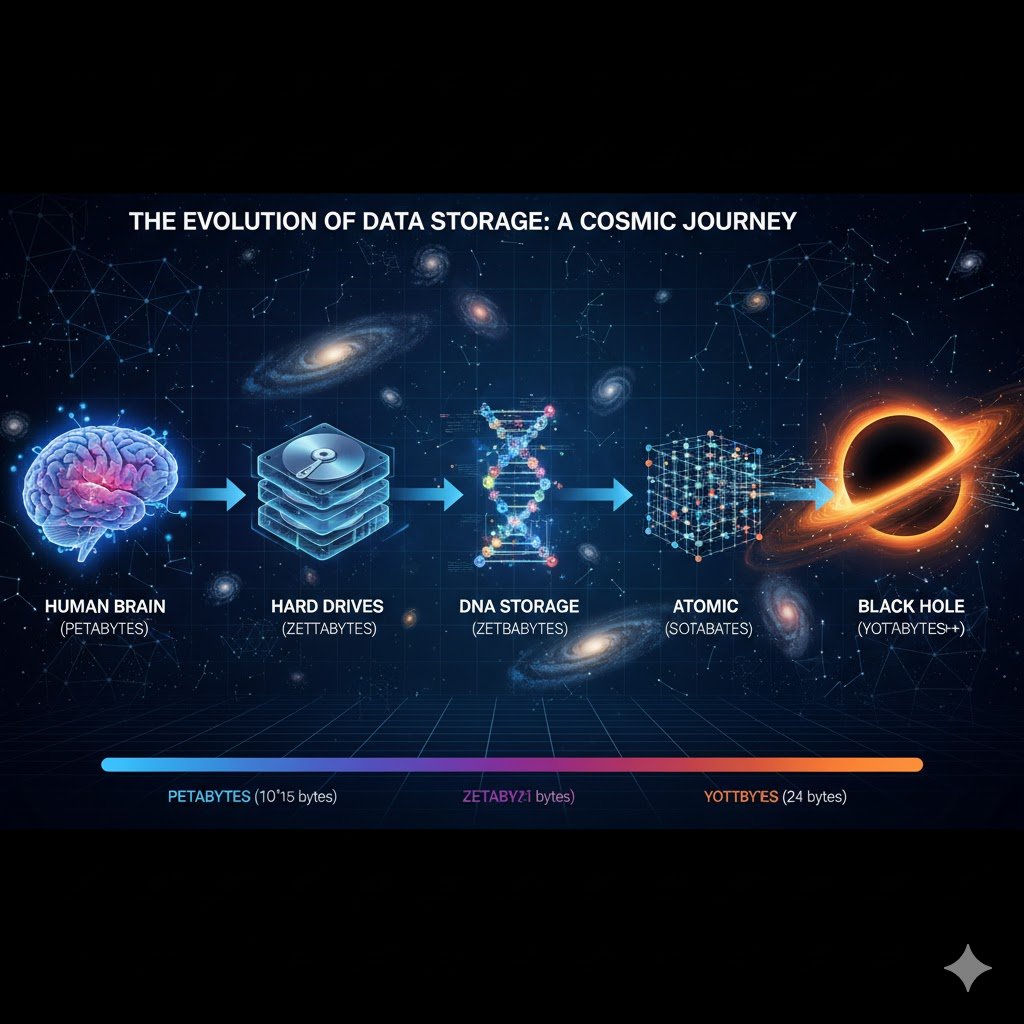

Yay for dynamic thoughts! But this blog is not brought to you by either Seagate or Western Digital. Let us not limit ourselves to typical computer storage technology. For example, we can go back to biology for inspiration and find we already have a very efficient way to store information: our DNA. DNA stores our genetic information in a sequential ladder with different combinations of four nucleotide bases: adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine. Each rung on the ladder has four possible base pair combinations, equivalent to two bits of information.

For humans, one DNA molecule has about 3.2 billion rungs, which means it can store 800 megabytes of information. And all of that info is packed into a tiny nucleus around 10 microns in diameter. So if we were to just fill our brain space with nuclei, we could store 2 zettabytes of data. That’s a 2 followed by 21 zeroes, and equivalent to 750 trillion eBooks.

We can also look at some up-and-coming computer storage technology. One example is magnetoresistive random access memory, or MRAM. Like HDDs, this tech stores data magnetically, but with a twist. Or should I say, a spin. Because instead of one magnetic layer, MRAMs typically have two, with an insulating layer in between. One layer of the magnetic sandwich is permanently magnetized in one direction, while the other’s magnetization changes depending on the bit’s state.

If a certain bit needs to be a 0, the corresponding spot on that second layer is magnetized in the opposite direction relative to the first. If it needs to be a 1, it’s magnetized in the same direction. And to swap a bit from 0 to 1, or vice versa, MRAMs manipulate the direction that the layer’s electrons are spinning through electric currents.

By controlling the magnetization of these bits using currents instead of magnetic fields, MRAMs avoid a lot of the technological limitations that HDDs have. This opens the door for high data densities. MRAMs are still mostly in the R&D phase, but there’s a lot of promise.

Recently, researchers at Kioxia built an MRAM prototype that can store 64 gigabits within an area smaller than the smallest grains of sand. If we could fill our brains with this cutting-edge stuff, we’d store 1.6 yottabytes of data, or 1.6 trillion bytes. That’s not only about a thousand times more eBooks than our DNA-storage system. It’s almost 9 times the amount of data that the entire world will generate in 2025!

Atomic Storage and Black Holes:

But we may be able to do even better than that… say, by mapping bits not onto microscopic switches, or teeny tiny sections of a magnetized disk, but onto single atoms. There are a bunch of ways to do this, but let’s look at one method done by scientists at the University of Alberta in 2018. They used hydrogen atoms to represent bits, placed on top of a thin piece of silicon. If an atom is in a certain spot, that’s a 1. If it isn’t there, it’s a 0. With this method, the team was able to achieve a data density around 47 times higher than our example SSD from earlier. So if we were to stuff our brains with this hydrogen atom tech, we could store 75 petabytes of data.

In other words, about 30 billion of those eBooks. Which is kind of a letdown after the other numbers we’ve thrown around. But that’s because this tech requires auxiliary parts to work, including that bed of silicon atoms for the hydrogens to sit on. To get numbers that are more fun, let’s pretend we could perfectly map one bit to one atom without any additional overhead. And to really push the limits, let’s use the atom with the smallest radius: helium.

If we replaced our brains with helium atoms… ignoring any weird laws of physics getting them that close together… we could store around a million zettabytes in our heads. That’s 5500 times more than the expected amount of globally generated data in 2025. And we can keep playing this game, and think about storing data in subatomic particles, like protons or electrons. Or even weirder stuff like quarks. But instead of going down that particular rabbit hole, let’s dive into another hole: a black hole. Black holes are the upper limit of how much information we can pack into a given space.

In other words, if we were to keep packing more and more info into our heads, eventually our heads would collapse into a black hole. To which I say, no thank you.

But if we could somehow live through that, we could actually calculate how much info our black hole brain could store, thanks to Jacob Bekenstein and Stephen Hawking. Through a combination of their work, we know the information density of a black hole… which stores its information not within its 3D insides, but just its 2D “surface”. Yes, that is weird. No, we don’t have time to get into how that works.

But it’s got something to do with gravity. If we use their math and treat our black hole brain as a sphere with the same volume as a human brain, we can estimate that this black hole brain can store around 10^55 terabytes of info. That’s 10 million trillion terabytes.

If we were to maintain our 2025 global data generation rate, it would take us 5.5 x 10^43 years to generate this amount of information. That’s so far in the future, it’s not just our star that will be dead. Basically, every star will be dead, and the universe will be in its Black Hole Era. That’s the actual scientific name, I swear. Now, using black holes to store information might sound like a fun “what if” thought experiment.

And to some extent, it is. But the idea holds more water than you’d expect. One researcher, Gia Dvali, has proposed a theoretical artificial neural network that can store information using gravity, just like black holes. Specifically, in this neural network, artificial synapses communicate through gravity rather than chemical or electrical signals. With this method, the neural network could achieve a similar style of information packing as a black hole, without actually being a black hole. Which, personally, I’d still turn down. Even if it would help me remember literally… anything. My head is Swiss cheese.

Conclusion:

The human brain is a marvel of natural engineering, able to store more information than most high-end hard drives, and it does so with incredible efficiency. Yet when we imagine replacing it with computers, DNA, atomic storage, or even black hole-level density, we see just how tiny and constrained our biology is compared to the ultimate theoretical limits. Whether measured in terabytes, zettabytes, or beyond, these thought experiments highlight both the ingenuity of evolution and the staggering potential of future storage technologies. Our brains may not be limitless, but they remain astonishingly powerful, and beautifully practical for navigating the real world.

FAQs:

1. How much information can the average human brain store?

Estimates suggest around 143 terabytes, equivalent to roughly 55 million e-books.

2. Are computer hard drives or SSDs more efficient than the brain?

Certain SSDs and experimental storage can hold more raw data than a human brain, but they lack the dynamic, adaptable processing of neurons.

3. Can DNA or atomic storage really store more than a brain?

Yes, DNA-based storage and atomic-scale methods could theoretically store orders of magnitude more data than a human brain in the same volume.

4. What is the limit of information storage in the universe?

The ultimate limit comes from physics itself—black holes represent the highest possible information density.

5. Why can’t we just replace our brains with massive storage devices?

Storage alone isn’t enough; brains process, adapt, and link information dynamically, which current storage devices cannot replicate.

6. Is it possible to ever have a brain that remembers literally everything?

In theory, with futuristic storage like subatomic or black-hole-inspired methods, the limits could be astronomical, but biology, physics, and practicality impose real-world constraints.